Andrea D. Rivera Martínez

Departamento de Psicología

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, UPR RP

Medio: Fotografía

Abstract

Since 2016, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico has experienced a period of political challenges along with a severe economic austerity. Given the unpromising projections, voices of resistance, anger, frustration, uncertainty, and hope are becoming increasingly visible on the island’s cities’ walls and spaces. Thus, based on the current situation of fiscal crisis, this visual essay narrates and documents the continuum of interpretations and opinions regarding the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) inscribed in the urban fabric over the past five years from now..

Keywords: street art, bankruptcy, fiscal crisis, austerity, Puerto Rico

Resumen

Desde el 2016, el Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico experimenta un período de desafíos políticos junto con una severa austeridad económica. Dadas las proyecciones, las voces de resistencia, ira, frustración, incertidumbre y esperanza son cada vez más visibles en las paredes y espacios de las ciudades de la isla. Por tanto, dada la situación actual de crisis fiscal, este ensayo visual narra y documenta el continuo de interpretaciones y opiniones sobre la Ley de Supervisión, Gestión y Estabilidad Económica de Puerto Rico (PROMESA) inscritas en el tejido urbano durante los últimos cinco años.

Palabras claves: arte callejero, quiebra, crisis fiscal, austeridad, Puerto Rico

“The city, however, does not tell its past, but it contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.”

Italo Calvino, Invisible cities, 1972

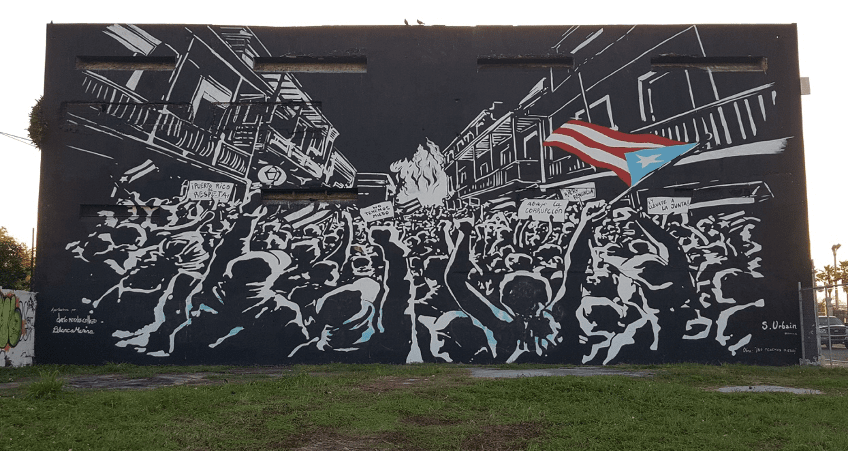

It was July 24th of 2019, before midnight in Old San Juan. Massive protest shouts took over the main street of the governor mansion, Calle de la Fortaleza, later soon renamed as Calle de la Resistencia in honor of the historical manifestation that was about to end. Countless Puerto Rican flags, even in gold, black, and with the representative colors of the LGBTQ community, were raised as a symbol of resistance after the release of what in no time became the global scandal of the RickyLeaks and the Telegramgate. Alongside protestors, the walls of the epicenter streets screamed what people and the worldwide Puerto Rican diaspora claimed in all possible and unimaginable ways. Graffitis, as well as posters, t-shirts, body paintings, live performances, music, and the popular cacerolazos,[i] followed the chant of Ricky Renuncia! of the latest days (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ricky Renuncia Movement Mural by S. Urbain, Calle del Tren, San Juan, Puerto Rico, February 3, 2020.

Note: The mural pictures Puerto Rico’s historical massive protest in the last spot of an encounter outside the governor’s mansion. The choice of a black background might be representing the night of protest before the release of the governor’s resignment announcement. The fire at the end of the painting could represent the victory of the Puerto Rican people even though La Fortaleza was never burned.

It’s been a year since then, but the memory continues as vivid as the burst of joy as soon as the Governor Ricardo Rosselló Neváres announced his resignation that late night. In the following days, from the two previous weeks of intense nationwide demonstrations, an inevitable question came to my mind. “Why street art has not prompted other significant social changes similar to Ricky Renuncia Moment, especially nowadays in times of fiscal crisis and austerity?” Going from the bottom up, in terms of the flow of information of what Chaffe (1993) called a medium of mass communication of low technology which emerges from below by grassroots, I decided to hear the public opinion through political writings of protest and resistance inscribed in the walls and corners of the city. However, to understand the complex sociopolitical panorama of Puerto Rico through the encounters with these messages of power struggles, I stepped back some years behind. This allowed me to understand the context of the expressions regarding what they say, and the change of course taken since then. Therefore, based on the current historical moment of bankruptcy, the starting point of this story begins with the dramatic announcement of, back then, Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla (2013-2016) after revealed the expected: the debt earned by the Puerto Rican Commonwealth was unpayable.

Historical Background: Setting the Action Scene

Since 2016, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico has survived a non-stop series of continuous struggles and experienced a period of political challenges along with severe economic austerity. The new economic, political, and social conditions have changed the urban environment and affected daily Puerto Rican lives on the island as well as the diaspora. In response to this period of crisis, various visual interventions have proliferated in the past six years. Expressions such as slogans, graffitis, murals, stencils, and paste-ups, among others, have expressed an overall discontent toward the corruption, negligence, indifference, and governmental taunt. However, the main focus of the discontent was the type of response of the federal government, followed by the island declaration of bankruptcy.

In 2016 the Congress of the United States of America imposed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). After many failed attempts by the governor at the time to renegotiate the terms of the government’s debt followed by the subsequent first default, the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico has also been the focal point of endless debates (Cabán, 2017 & 2018; De Los Ángeles-Trigo, 2016; Fonseca, 2019; Meléndez, 2018). PROMESA, as its name in Spanish indicates, is a federal law enacted to restructure the debt under the “promise” of the Federal government to restore the island's economic stability. To do so, it allows the board locally known as La Junta to oversee and manage the budget and finances of the island, as its official name reveals (De Los Ángeles-Trigo, 2016; Fonseca, 2019; Meléndez, 2018).

Streets have become a place of protest and political confrontation, that turned the capital of the island into a canvas of visible and divergent voices that demand to be heard. This scenario of protest is the direct result of the many disagreements related to the imposition of PROMESA in a democratic system. Even though Puerto Ricans elect their governors, every single decision taken by the government of Puerto Rico should be revised and approved by the board. In other words, the entity has the power to supersede local law in subject budget matters according to the fiscal plans. The disagreements over PROMESA are not exclusively due to its imposition above the vote of the islander’s electors. Even more, opposition to it has been generated predominantly in response to the austerity measures in which the board pretend to resolve the fiscal crisis (Cabán, 2017 & 2018; De Los Ángeles-Trigo, 2016; Fonseca, 2019; Meléndez, 2018).

I turned to street art to approach the issue of PROMESA, given its function as an open forum of communication accessible to everyone either from the car’s window, daily walks, or even as an online user through social media or internet search. I started my explorations through moving on foot with my camera, ready to shoot. However, throughout my way to Old San Juan from Río Piedras, I saw myself standing in between a sort of battlefield of different intertwined expressions competing with each other. What I thought I was understanding at the first glace turned to be something even more complicated to comprehend yet to explain. Wildly extended interpretations, opinions, and proposed actions against PROMESA and its board were inscribed on the city fabric.

Street Art of Resistance

The inscribed opinions about PROMESA in the island’s city fabric range along a continuum. The opposition toward PROMESA has been manifested by questioning democracy since the members of La Junta were not elected by the Puerto Rican people (Figure 2). For this reason, the board is also associated with dictatorship, given the board’s absolute control over the government’s budget and, therefore, on public policy (Figure 3). In addition to the expressions against the imposition of PROMESA and the excess of power holds by its board, other messages associate the law as a synonym of poverty (Figure 4). To describe this idea, people have used the widespread phrase: “They [the board] only want to count the register” to denounce the measurements of austerity and the intentions to leave the island impoverished. In fact, since 2016 PROMESA has not allocated federal resources to stabilize the island’s economy through economic development.

Figure 2: We do not understand this democracy. Wall painting artist: Unknown. Picture taken by René Álvarez, Calle Norzagaray, Old San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Note: The painting of the widely recognizable Lady Justice calls into question and criticizes the notion of the supposed representative democracy. The Lady (In)Justice intentionally has her blindfold slightly up and holds an unbalanced scale to illustrate that the "justice" is on the side of the bondholders' interests. In other words, whatever happens with the island's economy after the debt completion payments is not the board's business.

Figure 3: No to the fiscal control dictatorship by Francotiradores del Pincel, Jesús T. Piñeiro Ave, San Juan, Puerto Rico. September 23, 2019.

Note: As the bird of prey that feeds on dead animals, the buzzard on the left side of the wall painting represents investment firms that have been buying Puerto Rico debt at a highly discounted price to receive even more of the total debt original value by including interest. These are the creditors and bondholders of whom the government of Puerto Rico owes. The buzzard is holding a band which says: PROMESA board of control.

Figure 4: PROMESA of poverty. Stencil graffiti artist: Unknown. College of Humanities of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. February 06, 2020.

Other illustrations and writings refer directly to some members of the board, as some were actively involved in a substantive portion of the issued debt (Figure 5). Therefore, after considering the multimillion-dollar annual budget it is paid by the Commonwealth to it oversees, people’s opinions seem plausible that the board has gotten richer at the expense of what they have done and still do by “attempting” to resolve what they started (Meléndez, 2018). Followed by this latest line, many writings and wall paintings demand the debt audit to know precisely the amount earned illegally or not by the Puerto Rican government and the ones responsible for the debt (Figure 6). On the other side, some agreed the debt should not be paid, or merely, they believe that the board has to go (Figure 7).

Figure 5: The board chairman, José B. Carrión III. Installation artist: Unknown. Borinquen Alley in Río Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico. January 29, 2020.

Figure 6: Audit now. Graffiti writer: Unknown. Calle Marginal Baldorioty, San Juan, Puerto Rico. January 31, 2020.

Figure 7: ¡No to the debt! Graffiti writer: Unknown. Calle Norte San Juan, Puerto Rico. January 29, 2020.

Finally, some affirm that PROMESA is the long way result of the island’s colonial status. People who agree with this statement, assume that government’s debt is only the Americans' entire fault when the situation is both the result of the U.S. policies toward Puerto Rico and the local politics and the mismanagement of public finances (Figure 8). Some may have one or more of these divided opinions, but the debates still continue.

Figure 8: Wall painting artist: Unknown. Picture taken by René Álvarez, Calle Norzagaray, Old San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Confuse? Well, guess what, so do I. Until this point, the people general attitude toward PROMESA is still unclear. This lack of consent raises several questions: Could it be that the people of Puerto Rico want the members to be changed? Do they require an audit or a debt cancelation? Do they want the board to be gone? Or perhaps some or all of the above? Why are even they complaining about the board in the first place? Should not be the Congress where claims are addressed? After all, they hold power over La Junta. Any viewer could feel confused among so many dispersed arguments in different sectors of the capital’s urban landscape. Long before I could classify all these stances and even understand the uncertain status of the issue, I soon found myself stagnant among so many dispersed arguments in different sectors of the capital’s urban landscape. Rather than clearing the path out, street art was tangling me up in a growing web of confusing opinions coming from every direction. It took me a while to finally decipher what the city has been communicating behind its images and inscribed texts. Street art has shown the multiplicity of views that still exist over PROMESA but visually represented ever since in the urban scene. So, the confusion which I struggled so much with it may be the same one people have on a situation that remains in everyone’s lips, but that nobody has figured out how to resolve yet.

Despite the lack of consensus about PROMESA, it seems clear that street artists seek to create indignation and consciousness among the Puerto Rican people. Street artists feel the need to self-express and speak about socio-political problems that also affect and oppress them. Therefore, through their portrayals, they aim to make visible the different ways in which crisis and austerity permeate the life of every single inhabitant on the island. Thus, they claim the walls of the city to expose a reality that would never otherwise be expressed in the mainstream media. Consequently, the feelings that these expressions try to evoke may eventually become meaningful as a basis to create new conversations and raise questions.

Visual Encounters of Crisis: And the Struggle Continues

The course of street art also has changed in the last five years to denounce other social issues. As if it wasn’t enough, with the new political circumstances Puerto Rico was confronting with, simultaneously happenings in the subsequent years change the course of street art to denounce other social issues without losing PROMESA out of sight. The UPR systematic student strike took place on 2017 against the million-dollar cuts proposed by the board to the university system. On the island’s south, however, a growing resistance of another nature in the municipality of Peñuelas intensified due to the environmental and health threats of the dumping practice of toxic coal ashes in landfills (Figure 9). Lastly, in the upper northwestern of the island, a group of protestors fought to stop the construction of a tourist resort complex on the valuable ecological coastal zone of Playuela in Aguadilla. Inevitably, street art of political expression ceases after the hit of Hurricane Irma in the electricity infrastructure and the followed disaster left by Hurricane María across the entire island.

Figure 9: The only ashes we want are those from the board by El Colectivo La Puerta. Picture retrieved from the official Facebook page of El Colectivo La Puerta, Calle Marginal Baldorioty, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Note. The artists gave a twist to the resounded coal ashes situation in Peñuelas to keep carry on the message of denouncement against the board.

As Puerto Rico still recovering in 2018, so the expressive resistance through spray cans. During this year, the release of Harvard's study of Puerto Rico's Hurricane María death toll caused a scandal after the estimated calculation of 4,645 deaths, rather than the government official count of 64 deaths. Soon the 4,645 number became an immortalize symbol of remembrance graffitied on every city corner despite the later estimated death toll of 2,975 from a George Washington University study commissioned by the US Commonwealth. A year after Hurricane María another release, this time from a viral video on the social media, created even more disappointment and resentment. The video showed undistributed humanitarian aid in shipping containers parked at the offices of the state elections commission. The wasted donations for the Hurricane María victims, along with the subsequent viral of thousands of water bottles meant for hurricane survivors but abandoned on the naval base Roosevelt Roads, generated collective anger.

The Summer of 2019 was the moment where the patience of the people ran out. Puerto Rico's Former Secretary of Education Julia Keleher was arrested for corruption by the FBI. This news certainly angered people after she executed the massive close of hundreds of schools as part of the austerity measures. Also, the FBI effectuated a series of other arrests of the Rosselló's administration civil servants by the same motives-matter. However, what finally made Puerto Ricans erupt was the disrespectful Telegram chat messages between the governor and his inner circle of advisers. The leaked texts showed offensive remarks toward women, the LGBTQ community, people with disabilities, the obese, politicians, members of the media, celebrities, people whose houses were destroyed by hurricanes. The text's messages evidenced the ruthless and outrageous manner in which the Hurricane María deaths subject was treated. The chat also exposed the type of administration and leader who ran a country in crisis and revealed the dishonest strategies to advance their career and political campaign.

The Telegramgate: #Telegramgate #Rickyleaks #RickyRenuncia

The demand of Puerto Rican people was clear after the leak of the text messages between Roselló and members of his staff. In the modern Puerto Rican version of Watergate's scandal, the Puerto Rico's Center for Investigative Journalism publicly disclosed the private Telegram chat content through an anonymous source. After the release of such a document, the immediate response across the country's political spectrum was that Ricardo Rosselló had to resign his official duties as the Commander in Chief. To demand his resignation, people spontaneously mobilized daily massive protests and rallies through the use of social media. Soon the scandal became a trending topic under the creative hashtags to keep the issue showing up on mass media and, thus, it mobilize more people (Figure 10).

Figure 10: You see? Today we are not colors. We are Puerto Rico. Wall painting artist: Unknown. Calle del Tren, San Juan, Puerto Rico. February 3, 2020.

Note. The word “colors” have the colors that represent the three main political parties of Puerto Rico. Green is for the Independence Party; the Popular Democratic Party uses red and blue identifies the New Progressive Party. This message refers to the sense of unity of Puerto Ricans beyond ideologies and political parties by demanding the resignation of the former governor.

In contrast to PROMESA, Puerto Ricans came together under a single claim while they rise against the corrupt bipartisan government that had ruled the island for decades. The claim demanded was short and straight to the point and even catchy and easy to memorize: "Ricky Resign!" Given the indignation and collective anger, the claim was firm and clear, and there was no room for any other different claim from this one. The "Ricky Renuncia" was painted and pasted in every corner of the city. Moreover, since the message was addressed to Rosselló, the principal target place was La Fortaleza, where the island's governors officially reside.

Street Art and Multidirectional Country's Views Over PROMESA

Street art has been used to question and challenge the hegemonic power. However, street art on the island remains a mechanism of discharge rather than a tool for collective action given the discrepancies over PROMESA. The Ricky Renuncia Movement of 2019, as a historical framework, shows that the lack of a clear, definitive, well-defined message, oriented to action and strategically placed, provokes an effective massive response. As result, the different fragmented opinions all over the city create even more confusion and division between viewers in an already complex issue. Furthermore, the continuing bombing of different views about PROMESA makes people leave the issue aside, given the complexity of the subject. In the long way, the same disagreements respecting PROMESA makes street art to be indifferent to the viewer's eyes and consequently go unnoticed over time.

And this does not finish yet...

So far this year of 2020, a new set of events has changed street art courses to denounce other social conditions. One of these events was the seismic activity and subsequent aftershocks that hit the southwestern of the island but widely felt across the entire country. Hundreds of structures went down or suffered significant damages, and given the uncertainty of the next quake, people opted for protection in outdoor shelters. Also, social media video went viral back on after people found more humanitarian aid leftover from 2017's Hurricane María in a warehouse in Ponce. Followed by this discovery, people gathered and protested in front of the executive mansion as did with "Ricky Renucia," to demand the resignation of the former Governor's successor, Wanda Vázquez Garced. Soon after, the Covid-19 reached Puerto Rico.

Conclusion

The urban scenario demonstrates the multiplexity of interpretations and opinions that have been raise and took place in the island city walls since the very beginning of PROMESA. The federal law enacted to the Commonwealth's fiscal system has generated a spectrum of debates not only on the Island but on the mainland. The interpretations and proposed ways of action of the same subject matter compete with each other in the capital city urban landscape. Simultaneously, street art of political resistance in the island has changed to make room for other social significant concerns related or not with PROMESA according to what has happened ever since.

The Puerto Rican case coincide with the findings of Tsilimpounidi (2015), Karathanasis (2014), & Margulis (2009) with the Greek government-debt crisis. According to their research, the city expresses multiple aspects of social life, and therefore, it can be considered a decipherable text that can also be read and interpreted by the viewers. For them, the city does not only work but also communicates, and it can be perceived as a discourse that speaks to it inhabits. Several visual interventions in the city, whether artistically or not, narrates and illustrates conflicts and social criticism due, but not solely, by political decisions (Karathanasis, 2014). Although street art does not only express power struggles, in recent years, there has been a rise of several visual representations in city streets in response to social conditions related to crisis and social change (Karathanasis, 2014; Tsilimpounidi, 2015). In other words, the street has its own story, and the viewer can understand the social tendencies that involve each historical moment by looking at what has been written and painted on its walls (Tsilimpounidi, 2015). Therefore, street art of resistance in Puerto Rico provides a broader picture of how crisis, governmental deficiency and colonial status has affected Puerto Ricans. However, it has not helped to encourage a massive uprising against PROMESA, given the disagreements and subsequent happenings that have slightly deflected the public attention to other matters. So, after facing austerity, hurricanes, an intense national manifestation, earthquakes, and a worldwide outbreak along with a crushing debt over shoulders, one wonders: What's next?

References

Cabán, P. (2017). Puerto Rico and PROMESA: Reaffirming Colonialism. New Politics Journal, 14(3), 119-125. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/lacs_fac_scholar/25/

Cabán, P. (2018). PROMESA, Puerto Rico and the American empire. Latino Studies, 16(2), 161184. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-018-0125-z

Chaffe, G. L. (1993). Political protest and street art: Populart tools for democratization in Hispanic countries. Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Calvino, I. (1972). Invisible cities. Harcourt. Inc.

De los Ángeles Trigo, M. (2016). Los Estados Unidos y la promesa para Puerto Rico. América en Libros.

Fonseca, M. (2019). Beyond colonial entrapment: The challenges of Puerto Rican “national consciousness” in times of Promesa. Interventions, 21(5), 747-765. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2019.1585917

Karathanasis, P. (2014). Street art: graffiti, art, political protest and the street. [Exhibition catalogue]. Onassis Culture Centre.

Margulis, M. (2009). Sociología de la cultura: Conceptos y problemas. Editorial Biblos.

Meléndez, E. (2018). The politics of PROMESA. Centro Journal, 3(3), 43-71.

Tsilimpounidi, M. (2015). ‘If these walls could talk’: Street art and urban belonging in the Athens of crisis. Laboratorium, 7(2), 71-91. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303857429_'If_These_Walls_Could_Talk'_Str et_Art_and_Urban_Belonging_in_the_Athens_of_Crisis

Notes

[i] Cacerolazos, casserole in English, is a common form of protest by making noise with any kind of pans.

![[IN]Genios](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51c861c1e4b0fb70e38c0a8a/48d2f465-eaf4-4dbc-a7ce-9e75312d5b47/logo+final+%28blanco+y+rojo%29+crop.png?format=1500w)